Introduction:

The Queen Tin Hinan, a legendary figure from the 4th century, is considered the ancestor of the Tuareg people of North Africa. Known for her beauty, wisdom, and frequent travels, she is revered as "the mother of us all." Tin Hinan's origins are shrouded in mystery, with various oral traditions offering differing accounts of her life. Some say she was a princess exiled from the northern Sahara, while others believe she was a Berber Muslim from the Tafilalt oasis. In 1925, Byron Khun de Porok discovered her tomb in the Hoggar mountains, confirming her existence. However, little is known about her tribe, family, or cause of death. While historical documentation about her life remains sparse, archaeological and oral traditions have preserved her legacy. The tale of Tin Hinan presents a fascinating convergence of history, myth, and archaeology, shedding light on the cultural and political foundations of the Tuareg people.

The Queen Tin Hinan: making by the AI

I. The Legend of Tin Hinan:

Tin Hinan and the Tuareg people

1/ The Tuareg people: who are them?

Elegance | An amazingly elegant tuareg family ... created by Emilia Tjernström | Flickr

The Tuareg, also known as "the blue people of the Sahara," are a semi-nomadic, pastoralist Berber group primarily found in North Africa. Their name stems from the indigo turbans worn by men, which often stain their skin. Historically feared and respected, they controlled desert trade routes and resisted invasions from various empires, including the Phoenicians, Romans, and French. Today, the Tuareg number between 1.5 to 2.5 million, spread across countries like Algeria, Libya, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Nigeria. They are mostly Muslim and speak the Tamasheq language. Despite being a minority, they maintain a strong cultural identity, although political unrest has led many to migrate south.

2/The Queen Tin Hinan: Myth or Fact?

Tin Hinan, a legendary figure of the Tuareg people, has captivated imaginations and inspired both literary and scholarly works. Her enduring presence as a symbol of the Tuareg societal structure highlights her significance.

Etymologically, her name derives from the Tamasheq roots "ti" (feminine singular pronoun "she"), "n" (possessive preposition "of"), and "ihinan" (plural noun from the verb "han", meaning "to migrate or move"). Together, Tin Hinan means "she of the journeys" or "the migrant." This interpretation emphasizes her connection to a nomadic lifestyle central to the Tuareg culture.

The legend recounts her arrival in the Ahaggar region from Tafilalet (Morocco) with her servant Takammat, who saved their caravan by finding food in an anthill. Upon settling, they encountered a local population described as primitive hunters and gatherers. Over time, Tin Hinan is said to have introduced the camel, fundamentally shaping the local way of life.

Historically, references to Tin Hinan have been intertwined with myth. Ibn Khaldoun, for instance, associates her with "Tiski the Limping Woman," an ancestor of veiled Sanhadja tribes, while archaeological findings date her tomb in Abalessa to the 4th century CE. The discovery of a skeleton believed to be hers included artifacts reflecting North African and Sudanese influences.

Anthropological studies on her remains have sparked debate, with some scholars questioning her gender based on skeletal features, despite the presence of traditionally feminine burial objects. Oral traditions further complicate her narrative, blending historical, mythological, and symbolic elements.

Tin Hinan serves as more than an individual; she embodies the Tuareg identity and matrilineal traditions. Her legend is reflected in similar myths of female founders across Tuareg society, reinforcing the role of women in the preservation of culture, land inheritance, and societal order.

II. Historical and Archaeological Context:

The discover Tin Hinan's tomb

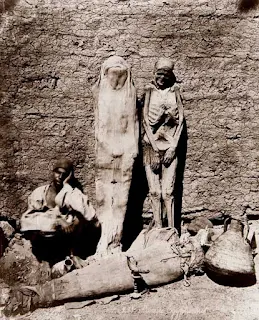

Burial of Tin Hinan (Bardo Museum, Algiers) published by Yelles/ Wikimedia Commons

The mausoleum of Tin Hinan, first discovered in 1925 by a Franco-American mission. The Count Byron Khun de Prorok, a Polish-American amateur archaeologist, unearthed a monumental circular tomb in Abalessa, southern Algeria, during a Saharan expedition supported by French authorities. Measuring 4 meters in height and 23 meters in diameter, the tomb is traditionally believed to be that of Tin Hinan. and later in 1933 by Maurice Reygasse, remains shrouded in mystery. Tin Hinan, regarded as the legendary ancestor of the Tuaregs of the Ahaggar, continues to raise numerous archaeological and historical questions. Oral traditions among the Tuaregs about her are often contradictory, and the evolving nature of oral history fails to provide definitive answers. According to eyewitnesses, the mausoleum, before its excavation, appeared as an unstructured heap of stones and earth with no clear architectural features. Yet, it was attributed symbolic or spiritual significance by locals.

The initial excavations revealed rooms and a burial chamber covered with large stone slabs, beneath which a skeleton was found alongside jewelry and valuable items. Later studies confirmed that this mausoleum was neither a fort nor a kasbah but part of the protohistoric Berber funerary architecture, similar to structures found in Tafilalet, Mauritania, and northern Algeria.

Ancient manuscripts mention Tin Hinan as a prominent historical figure, but the dates cited, such as her presence in Tidikelt in the 17th century, conflict with carbon-14 analysis, which dates her death to around the 5th century CE. Despite this, these manuscripts, most of which are modern copies, highlight the symbolic importance of this figure, even though they lack precise historical reliability.

Anthropological studies revealed that Tin Hinan was tall (172–175 cm) and suffered from conditions that caused her to limp. Her pelvis exhibited ambiguous characteristics, suggesting she may not have borne children. However, Tuareg oral traditions claim that the nobles of the 18th century were direct descendants of her, despite a 13-century gap between her era and theirs.

This chronological gap raises questions about how her memory was transmitted and how collective identity was constructed. While the matrilineal traditions of the Tuaregs are symbolically linked to Tin Hinan, no clear evidence connects her to a biological lineage. This cultural trait, unique to the Tuaregs, contrasts with the dominant patriarchal practices of other Berber societies.

Despite archaeological discoveries and anthropological studies, Tin Hinan’s story remains partially enigmatic. Her legendary role and the affection she inspires among an entire people reflect her symbolic significance, but questions about her geographical, ethnic, and historical origins remain unresolved.

III. Contemporary Relevance:

Tin Hinan The Cultural Icon of the Tuareg People

Tuareg Nomads | In the Saharan Desert part of Mali, a man shelters… created by Bradley Watson| Flickr

Tin Hinan is recognized as a central historical and cultural figure among the Tuareg people. Her achievements, particularly as a woman from a foreign land, were remarkable given the sociopolitical challenges and gender dynamics of her era. Historical narratives attribute to her a combination of wisdom, intelligence, courage, and resilience, qualities that enabled her to overcome opposition, gain the trust of the local population, unite them, and ascend as their leader. Her legacy endures, with annual festivals held in her honor in the oasis city of Tamanrasset, Algeria, from February 20 to 28.

Tin Hinan is often referred to by contemporary Tuareg communities as the "African Amazon Queen," highlighting her reputed prowess as a warrior. Additionally, she is credited with possessing extensive knowledge of herbal medicine, healing practices, and the teaching of poetry and the Tifinagh alphabet, the traditional script of the Tuareg. Her most significant accomplishment was the unification of the Tuareg people and the establishment of a kingdom in the Hoggar region. Her daughter, Kella, is traditionally regarded as the founder of the Kel Rela tribe.

Under Queen Tin Hinan's leadership, the Tuaregs established vital caravan trading routes, which facilitated substantial economic prosperity and wealth during the 4th and 5th centuries CE. While Tin Hinan is broadly recognized as the founder of the Tuareg confederation, it is suggested that the Ihadanaren tribe directly descends from her, whereas the plebeian tribes of Dag Rali and Ait Loaien are believed to have descended from her companion, Takamat. This enduring historical and cultural significance underscores Tin Hinan's role as a foundational figure in Tuareg heritage.

Conclusion:

While archaeology seeks to distinguish historical fact from legend, the myth of Tin Hinan continues to be a living model of Tuareg ideology and cultural resilience. As a Tuareg elder aptly remarked, “Tin Hinan is like the air we breathe; she is everywhere in the Ahaggar.”

Her legacy, encapsulated in the stories of her wisdom and strength, endures as a symbol of Tuareg unity, matrilineal heritage, and resilience. As both a historical and mythical figure, Tin Hinan's influence on the Tuareg people is profound and her story continues to inspire future generations.

Bibliography:

- Bovill, E.W. The Golden Trade of the Moors. London: Oxford University Press, 1958.

- Lhote, Henri. The Search for the Tassili Frescoes. New York: Dutton, 1959.

- Prorok, Byron Khun de. Mysterious Sahara: The Land of Gold, of Sand, and of Ruins. London: Hurst & Blackett, 1929.

- Nicolaisen, Johannes. The Pastoral Tuareg: Ecology, Culture, and Society. London: Thames and Hudson, 1963.

- Camps, Gabriel. Les Berbères: Mémoire et identité. Paris: Errance, 1980.

- Werner, Louis. "The Legendary Queen Tin Hinan." Saudi Aramco World, 1998.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

._Wellcome_V0004455.jpg)

.jpg)